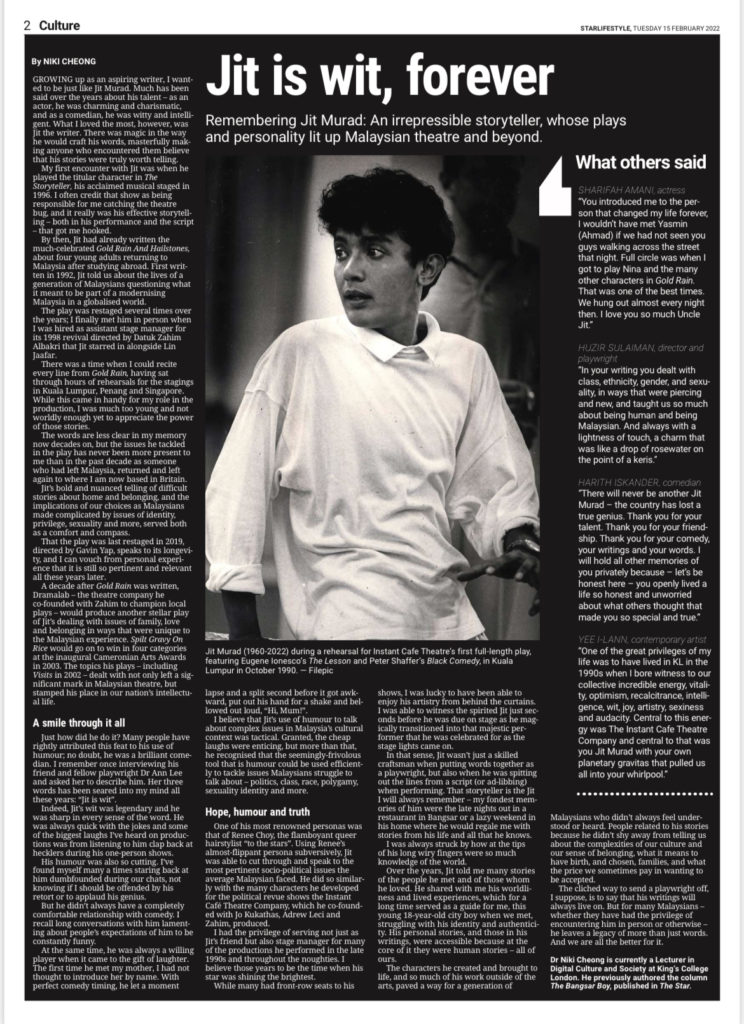

The Star invited me to write a tribute to my friend, Jit. This article was originally published here. The following is the original text I had written.

BY NIKI CHEONG

Growing up as an aspiring writer, I wanted just to be like Jit Murad. Much has been said over the years about his talent – as an actor, he was charming and charismatic, and as a comedian, he was witty and intelligent. What I loved the most, however, was Jit the writer. There was magic in the way he would craft his words, masterfully making anyone who encountered them believe that his stories were truly worth telling.

My first encounter with Jit was when he played the titular character in The Storyteller, his acclaimed musical staged in 1996. I often credit that show as being responsible for me catching the theatre bug, and it really was his effective storytelling – both in his performance and the script – that got me hooked.

By then, Jit had already written the much-celebrated Gold Rain and Hailstones, about four young adults returning to Malaysia after studying abroad. First written in 1992, Jit told us about the lives of a generation of Malaysians questioning what it meant to be part of a modernising Malaysia in a globalised world.

The play was restaged several times over the years; I finally met him in person when I was hired as assistant stage manager for its 1998 revival directed by Datuk Zahim Albakri that Jit starred in alongside Lin Jaafar.

There was a time when I could recite every line from Gold Rain, having sat through hours of rehearsals for the stagings in Kuala Lumpur, Penang and Singapore. While this came in handy for my role in the production, I was much too young and not worldly enough yet to appreciate the power of those stories.

The words are less clear in my memory now decades on, but the issues he tackled in the play has never been more present to me than in the past decade as someone who had left Malaysia, returned and left again to where I am now based in Britain. Jit’s bold and nuanced telling of difficult stories about home and belonging, and the implications of our choices as Malaysians made complicated by issues of identity, privilege, sexuality and more served both as comfort and a compass.

That the play was last restaged in 2019, directed by Gavin Yap, speaks to its longevity, and I can vouch from personal experience that it is still so pertinent and relevant all these years later.

A decade after Gold Rain was written, Dramalab – the theatre company he co-founded with Zahim to champion local plays – would produce another stellar play of Jit’s dealing with issues of family, love and belonging in ways that were unique to the Malaysian experience. Spilt Gravy on Rice would go on to win in four categories at the inaugural Cameronian Arts Awards in 2003. The topics his plays – including Visits in 2002 – dealt with not only left a significant mark in Malaysian theatre, but stamped his place in our nation’s intellectual life.

Just how did he do it? Many people have rightly attributed this to his use of humour; no doubt, he was a brilliant comedian. I remember once interviewing his friend and fellow playwright Dr. Ann Lee and asked her to describe him. Her three words has been seared into my mind all these years: “Jit is wit”.

Indeed, Jit’s wit was legendary, and he was sharp in every sense of the word. He was always quick with the jokes and some of the biggest laughs I’ve heard on productions was listening to him clapback at hecklers during his one-person shows. His humour was also so cutting. I’ve found myself many a times staring back at him dumbfounded during out chats, not knowing if I should be offended by his retort or to clap at his genius.

But he didn’t always have a completely comfortable relationship with comedy. I recall long conversations with him lamenting about people’s expectations of him to be constantly funny. At the same time, he was always a willing player when it came to the gift of laughter. The first time he met my mother, I had not thought to introduce her by name. With perfect comedy timing, he let a moment lapse and a split second before it got awkward, put out his hand for a shake and bellowed out loud, “Hi, mum!”

I believe that Jit’s use of humour to talk about complex issues in Malaysia cultural context was tactical. Granted, the cheap laughs were enticing, but more than that, he recognised that the seemingly-frivolous tool that is humour could be used efficiently to tackle issues Malaysians struggle to talk about – politics, class, race, polygamy, homosexuality and more.

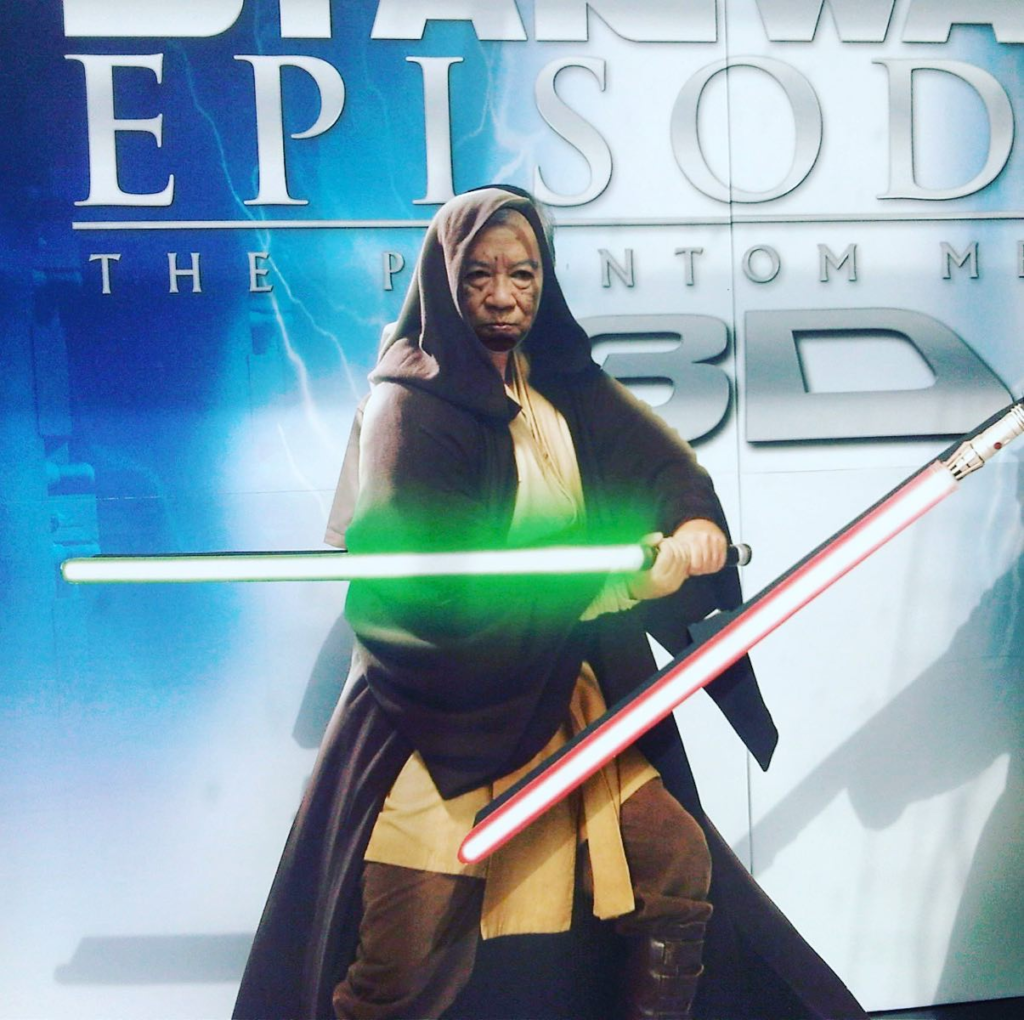

One of his most renowned personas was that of Renee Choy, the flamboyant queer hairstylist “to the stars”. Using Choy’s almost-flippant persona subversively, Jit was able to cut through and speak to the most pertinent socio-political issues the average Malaysian faced. He did so similarly with the many characters he developed for the political revue shows the Instant Café Theatre Company, which he co-founded alongside Jo Kukathas, Andrew Leci and Zahim, produced.

I had the privilege of serving not just as Jit’s friend but also stage manager for many of the productions he performed in the late 1990s and throughout the noughties. I believe those years to be the time when his star was shining the brightest.

While many had front-row seats to his shows, I was lucky to have been able to enjoy his artistry from behind the curtains. I was able to witness the spirited Jit just seconds before he was due on stage as he magically transitioned into that majestic performer that he was celebrate for as the stage lights came on.

In that sense, Jit wasn’t just a skilled craftsman when putting words together as a playwright, but also when he was spitting out the lines from a script (or ad-libbing) when performing. That storyteller is the Jit I will always remember – my fondest memories of him were the late nights out in a restaurant in Bangsar or a lazy weekend in his home where he would regale me with stories from his life and all that he knows. I was always struck by how at the tips of his long wiry fingers were so much knowledge of the world.

Over the years, Jit told me many stories of the people he met and of those whom he loved. He shared with me his worldliness and lived experiences, which for a long time served as a guide for me, this young 18-year-old city boy when we met, struggling with his identity and authenticity. His personal stories, and those in his writings, were accessible because at the core of it they were human stories – all of ours.

The characters he created and brought to life, and so much of his work outside of the arts, paved a way for a generation of Malaysians who didn’t always feel understood or heard. People related to his stories because he didn’t shy away from telling us about the complexities of our culture and our sense of belonging, what it means to have birth and chosen families, and what the price we sometimes pay in wanting to be accepted.

The cliched way to send a playwright off, I suppose, is to say that his writings will always live on. But for many Malaysians – whether they have had the privilege of encountering him in person or otherwise – he leaves a legacy of more than just words. And we are all the better for it.

Dr. Niki Cheong is currently Lecturer in Digital Culture and Society at King’s College London. He previously authored the column The Bangsar Boy, published in The Star.